This is a refreshed version of an old article from our original blog, the one where all the images were unfortunately lost. Today, one of our clients needed a primer on best practices for user login. I thought it was a good time to revisit this topic and discuss the changes that have occurred in the 12 years since that original article was published.

Hashing versus Encryption

Hashing is a one-way encryption, implying that even with knowledge of the algorithm and salt phrase used for hash creation, it is impossible to revert it back to the original string. In contrast, standard encryption is a two-way function, allowing the conversion back to the original string if the algorithm is known. If you need to store documents or information for future use, encryption is the appropriate method. However, if your sole purpose is to confirm the correct password entered by a user, hashing is the ideal solution.

Storing the hash of a password enhances security. When a user logs in, the system compares the hash of the entered password to the hash stored in the database. This might seem similar to encryption, but the difference becomes apparent during a security breach.

Suppose a hacker obtains a portion of your user list, including their passwords. Even if these passwords are encrypted, a skilled hacker could potentially reverse the encryption within a few hours.

At this point, you might decide to reset everyone’s passwords. While this would secure your site, it doesn’t solve the problem entirely, as many people use the same password for multiple sites. Thus, the hacker could use the compromised data to access other sites, such as email accounts or banks.

Should the breach be traced back to you, the consequences could be severe. However, if you had stored passwords as hashes, the hacker would not be able to decrypt them and obtain the actual passwords.

However, you’re not completely safe yet. Two different strings can produce the same hash, a phenomenon known as a collision. Therefore, if a hacker invests in even more GPUs and a tool called a rainbow table, they could persist until they find a second string that creates the same hash. Once they succeed, they can resume their malicious activities.

How about adding a little Salt to your Hash? Salt is used to fortify the hashing algorithm against collisions and rainbow tables. When a Salt phrase is used, a hacker cannot generate a matching collision, as the Hash on your system will differ from theirs. However, there remains one vulnerability. If a hacker manages to compromise your Salt phrase, they could potentially brute force their way to strings that generate the same hash.

The final piece of the puzzle is to use a unique salt phrase for each password. This way, even if an attacker spends significant time and resources to brute-force a matching password, only that one account is compromised. Each account requires the same amount of effort to breach because each uses a different salt phrase.

Implementing Hashes in WL

Now that we have some background, let’s look at implementing this in a WEBDEV application. We’ll examine the implementation that’s in place with our wxSocial demo. This example uses our wxFileManager classes. However, you should be able to implement the same underlying code in a non-wxFileManager project with minimal effort.

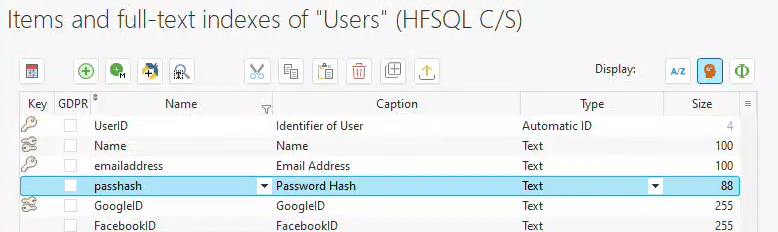

First, we need an 88-character string in our database table to store the hash.

How was that size determined? We’re using the HMAC-SHA512 algorithm to generate the hash. The 512 indicates that it’s a 512-bit hash. If you divide 512 by 8, you get 64.

But why 88? We plan to store the hash in Base64 encoding. Handling binary data across multiple operating systems, REST services, databases, etc., can be challenging, so storing it in an already encoded form simplifies the process. The Base64 encoded version of a string will be (4*Length)/3, then rounded up to the next multiple of 4 to account for padding. So, 64*4 equals 256, divided by 3 equals approximately 85.33. Rounded up to the nearest multiple of 4, we get 88. If you don’t believe it, feel free to Google it 🙂 This calculation assumes we are using Base64 encoding without carriage returns.

Now, we just need a couple of simple functions. As previously mentioned, because I am using wxFileManager, I’ve implemented these as properties and methods in my record class. However, they could just as easily be made into linear procedural calls.

Our first one will be a property that is used to set the password when creating the account.

PROCEDURE ClearPassword(Value)

IF UserID = 0 THEN

Info("Can't Set Password until user is saved")

ELSE

passhash = Encode(HashString(HA_HMAC_SHA_512,Value ,NumToString(UserID)),encodeBASE64NoCR)

END

Note that this property only includes a write (set) function. When we set ClearPassword to the value that the user types as the password, it generates a hash, encodes it in Base64, and stores it in the passhash field. If the UserID is 0, the code will generate an error, because use the UserID as the salt for each hash, ensuring each hash has its unique salt.

💡 Properties are one of the features I appreciate most about classes. A property is a function that can be referenced as if it were a variable, making it bindable to screen controls and more. When you reference the variable, the property's function is executed.

A property has both a "Get" and a "Set" function. When you reference a property (e.g., Info(MyProperty)), the "Get" function is invoked and MyProperty is the returned value. When you assign a value to the property (e.g., MyProperty = "ABC"), the "Set" function is executed, with the assigned value passed as a parameter.

This allows complex logic to be tied to properties, enabling another programmer to use it like any other variable without needing to understand all the underlying complexities.

Next, we need a method to validate the password when a user attempts to log in.

FUNCTION isPasswordValid(inPassword is string)

IF NoSpace(inPassword) = "" THEN

RESULT False

END

IF Encode(HashString(HA_HMAC_SHA_512,inPassword ,NumToString(UserID)),encodeBASE64NoCR) = passhash THEN

RESULT True

ELSE

RESULT False

END

We prohibit blank passwords, which is what the first IF statement ensures. Next, we generate the Base64 Encoded hash in the same manner as before and compare it to the one that’s stored.

All that’s left is to implement these within our code. The save button on the user form contains the following code:

PageToFile()

mgrUser is UsersManagementClass

IF NewUser THEN

mgrUser.SaveRecord(Glo.recUser,0,WXManagerClass.eAdd)

ELSE

mgrUser.SaveRecord(Glo.recUser,Glo.recUser.UserID,WXManagerClass.eChange)

END

// Have to Update Password after creating the user, because the UserID is used for the hash

IF ckResetPassword THEN

tmpPassword is string = NoSpace(edtPassword)

IF tmpPassword <> ""

Glo.recUser.ClearPassword = tmpPassword

ELSE

Glo.recUser.passhash = ""

END

mgrUser.SaveRecord(Glo.recUser,Glo.recUser.UserID,WXManagerClass.eChange)

END

Saving the user first is crucial when adding a new user since we use the USERID as the salt for hash generation. If we tried to generate the hash before saving, the hash would use “0” for the salt, which would fail when validating the password since it would use the correct UserID as the salt. The message in the property serves as a reminder to avoid coding out of order. Ideally, this should be an assert, not requiring user interaction, but in this simple example, any issues would likely surface early in testing.

We assign the ClearPassword property with the password that the user has entered. You might wonder why I first transfer the edit control value into a string variable. This is because I’ve encountered issues where the hashes aren’t generated identically when referencing an edit control directly. Therefore, it’s better to transfer them into a string to ensure their proper definition.

In this wxSocial example, I permit the saving of an empty password because the user might choose to not have a local password, opting to only use social logins instead.

The following code is behind our Login button.

PageToFile()

tmpPassword is string = NoSpace(edtPassword)

// Look For User Record

mgrUser.Filterstring = [

WHERE emailaddress = '[%NoSpace(edtEmail)%]'

]

mgrUser.FetchData()

IF ArrayCount(mgrUser.arrRec) = 1 THEN

Glo.recUser = mgrUser.arrRec[1]

IF Glo.recUser.isPasswordValid(tmpPassword) THEN

Check2FA()

ELSE

VariableReset(Glo.recUser)

Info("Sorry we are unable to verify you login information, please try again.")

RETURN

END

ELSE

Info("Sorry we are unable to verify you login information, please try again.")

RETURN

END

We transfer the password entered by the user into a string variable. We retrieve the user record based on the provided email address. Then, we use the isPasswordValid method to validate the password. The Check2FA() function will be discussed in an upcoming article.

What’s Next

These are the basic best practices for managing user passwords and storing them as hashes. Storing passwords in hash form ensures that even you, the developer, can’t decipher the user’s password. This necessitates a secondary validation method to allow users to reset their passwords if forgotten. You’re probably familiar with these ‘password reset’ emails and text messages. We use Mailgun, Nexmo, and Twilio for these purposes and have dedicated classes for each.

We could make this even more secure by using a unique field for each user not stored in the same table as the hash to further complicate compromising the hash, but that is a bit overboard for this example

Depending on your use case, Incorporating a social login option into your application, instead of offering local passwords, can eliminate the need for password management. This is akin to outsourcing your credit card processing to a third party and storing only tokens in your database to reduce liability.

Implementing two-factor authentication (2FA) is another option demonstrated in the wxSocial application. This can be achieved either by receiving a code via email or text, or by pairing with an Authenticator application. I will soon post another article showing how to integrate Authenticator apps.

The holy grail of password management is a concept formerly known as “Passwordless,” now referred to as “Passkeys”. These are not only difficult to spoof or steal, but they also make it easier for the user to log in. I’m preparing an article exploring how to implement Passkeys in WEBDEV.

This example is from our wxSocial project, which you can view online at https://wxsocial.wxperts.com/. The project employs several of our helper classes to streamline the management of OAuth and OpenID communications, HTTP communications, JSON Web Tokens, and Cookie Management.

wxPerts offers these classes, along with other 3rd party API classes, to our consulting and mentoring clients. If you’re interested in integrating any of these classes, please contact us at sales@wxperts.com.

One thought on “Password Hash Primer for WEBDEV”